When used properly, an alarm system can be a vital life safety tool. The downside is that, when not used properly, alarm systems can waste precious resources, requiring police to respond when no real emergency is present. At times, this reality has created tensions between the alarm industry and public safety personnel — but over time, the alarm industry has taken a number of steps to prevent false dispatches, and those efforts have yielded gradual but steady results.

“Nobody benefits from a false alarm — not the citizen, the alarm industry or public safety,” emphasizes Jim Cogswell, special services officer for the Leawood, Kan., Police Department as well as president of the False Alarm Reduction Association, a public safety organization aimed at reducing false alarms.

People within the public safety community and alarm industry like to distinguish between false alarms, where an alarm goes off when there is no emergency, and false dispatches, where public safety is sent to respond to such an alarm. “Today we are seeing residential false dispatch rates in the 0.2 to 0.25 range,” says Stan Martin, executive director of the Security Industry Alarm Coalition, a group comprised of members of several key alarm industry associations with the goal of reducing false alarms. A rate of 0.2 or 0.25, he explains, “means that people have a dispatch to the home only once every four to five years.” Nationwide, Martin adds, the false dispatch rate is around 0.3 for residential users and slightly more than 1 for commercial accounts.

Over the last eight years, the false dispatch rate has decreased 40 percent to 50 percent during a period when the total number of systems in operation has grown from 17 million to 34 million systems, Martin relates. He adds that the reduction is really more in the range of 70 percent when those growth numbers are figured in. “The impact is much greater when you realize that we doubled the number of systems in eight years,” Martin calculates.

Most stakeholders agree there’s no single solution that has contributed to this improvement. As Steve Doyle, executive vice president of the Central Station Alarm Association (CSAA) puts it, “There’s a whole host of different things involved, starting from the equipment, policies and procedures, customer training, alarm verification calls and working with the AHJ,” he comments. The latter acronym refers to the “authority having jurisdiction” — whatever local government provides public safety for an area. “You can’t point your finger to one thing,” Doyle says. “There’s a combination of things that have made the industry more responsive and made the AHJs much more aware that there is no quick fix.”

TACTICS

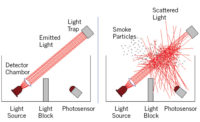

The alarm industry has undertaken many initiatives to reduce false alarms and false dispatches. One ap-proach to reducing false dispatches that continues to gain momentum is enhanced call verification. Traditionally, when an alarm signal comes into a central station, central station operators call the premises to see if someone is available to provide the correct passcode and, if not, the police are dispatched. With enhanced call verification, at least one additional call is made, according to instructions left by the alarm subscriber with the central station. When owners are reached on their cell phone or at another number, they often advise central station operators not to dispatch. An example would be if the owner receives the call at the same time a new babysitter was expected to arrive.

When a central station implements enhanced call verification, also known as multi-call verification, Martin says it will typically see a 30 percent to 50 percent reduction in false dispatches. “If dealers are not instructing their monitoring center to make a second call, they’re wasting a lot of resources,” he says.

Some dealers resist enhanced call verification because they may have tried it five to 10 years ago and not found it to be effective. But Martin encourages them to try again, now that so many customers have cell phones. Indeed, he says, “Some companies are now starting to call the cell phone to start with.”

Some of the most recent successes in reducing false alarms have resulted from greater cooperation between the public safety community and the alarm industry, Martin conveys. The alarm industry’s initial attempts to bring the two groups together involved inviting police chiefs to alarm industry functions. But, Martin recalls, “That didn’t stick — we couldn’t draw chiefs into alarm industry meetings.”

More recently, Security Industry Association (SIA) began setting up statewide alarm management committees through state chiefs of police organizations. “We have 12 operating now,” Martin discloses, adding that another six are in the process of being created. “You keep working at it and you find the model that works. It’s a wonderful application of a public/private partnership.”

A typical committee consists of three police chiefs and three members of the state alarm association. “The main goal is to establish communication between the alarm industry and law enforcement to work out issues,” Martin says. “If there are issues, they have a place to communicate and exchange information.”

Another goal of the committees is to facilitate the adoption of statewide false alarm regulation, ensuring consistency from AHJ to AHJ. “When the alarm industry and chiefs of police go to legislators together, you typically have smooth sailing,” Martin explains.

THE PUBLIC SAFETY VIEW

One police chief who has been involved in a statewide alarm management committee is Louis Dekmar of La Grange, Ga. Georgia’s committee was created a few years ago and has had a major impact on reducing false dispatches in the state.

Dekmar explains, “Through collaboration, we endorsed enhanced call verification, developed an educational brochure and developed a model ordinance and policies.” Ordinances such as the one Dekmar describes specify a program for fining customers that have a lot of false alarms.

The program was piloted in several communities, including La Grange, and as a result, Dekmar says, “We saw a reduction of false alarms of between 25 percent and 28 percent.”

Leawood also witnessed a large decline in false dispatches when it implemented a similar program, Cogswell says. Leawood’s false alarm ordinance dates back to 1994. Between 1995 and 2003, he says, “We saw a steady increase in the number of alarm systems installed and registered and a flat line for the number of calls for service.”

Since 2003, as alarm companies increasingly have been installing panels meeting the CP-01 standard developed by the American National Standards Institute and SIA, Leawood saw false dispatches decline even further. That standard eliminates features such as a “duress” code for disarming the system that tends to cause false alarms.

In 2007, a change in the Leawood ordinance came into effect that required alarm companies to use second-call verification, and that too has improved false dispatch rates. Today, Cogswell says, “We’re dropping on average a half percent per year on dispatch requests.” He notes that monitoring centers today stop as many as 85 percent of alarm systems from generating a dispatch.

“In Leawood, we’ve noticed that the number of users that have no false alarms during the year continues to grow,” Cogswell adds. Last year, he says, that included almost 80 percent of registered users. “If we dispatch and it’s a non-emergency and the monitoring center cancels the alarm before our officers arrive, we don’t count it,” he explains. “As you get fewer alarms and better response times, we beat the monitoring personnel sometimes.”

Some might say that’s a nice problem to have. “Last year our response time was under five minutes for an alarm,” Cogswell relates — an impressive number in a 15-square-mile city of 32,000 people.

Cogswell also likes to see alarm companies follow up with customers that have had false dispatches. Companies without their own central station can get reports from their wholesale central station, which advise them about which customers had their second false alarm in a year — and Cogswell advises them to use that information to work with those customers to try to correct the situation.

“We’ve had great success with false alarm school,” he says. In Leawood, any customer who has had two false alarms in a calendar year must attend the two-hour school, which is taught by instructors from the local alarm association.

“We worked with the Kansas City Burglar and Fire Alarm Association to develop the course content and five or six cities use pretty much the same format,” Cogswell recalls. The course, which is offered once a month on a weekday evening or Saturday morning, covers everything from how alarm panels and motion detectors work to why a false alarm wastes time and money.

The CSAA also offers an alternative to a live class for educating customers about false alarms. The organization has developed an online class, which it has made available to the International Chiefs of Police.

NON-RESPONSE

In recent years, some municipalities have taken a very different approach towards reducing false dispatches — they have refused to dispatch on an intrusion alarm unless a possible intruder was verified, typically through a video link between the central station and the alarm system. But that approach is on the wane, sources say.

“We can categorically call that solution a failure,” Martin says. “If there’s a good idea out there, it catches on within a couple of years, but only a handful of communities adopted this and several have reversed their position. Law enforcement has rejected it as a viable solution.”

He points to Dallas, where criminal activity increased after the city adopted a non-dispatch policy. “People were responding to their own alarms at great risk,” Martin divulges. “Several found bad guys and encountered life-threatening situations.”

The city also lost more than a million dollars in fines and permit fees. “You’re not laying off police officers; you’re just doing away with revenue,” Martin says.

Dallas ultimately reversed its position on false alarm verification, and Martin expects other AHJs to follow. He also expects to see more state-level solutions that use the public/private partnership approach that is working so well in Georgia and elsewhere.

Despite the widespread success at reducing false dispatches, there’s still room to improve, sources say. Martin would like to see heavier use of enhanced call verification among third-party central stations. Cogswell would like to see a greater focus on national retail chains. “When you’re sitting at home and get a bill for $50 for a false alarm fine, that’s a lot of money,” he says. “When you’re running a restaurant doing five million a year, $50 seems like nothing. And when you have a company with 1,000 locations nationwide and each has 10 false alarms, that’s a lot for everyone.”

One local chain restaurant in Leawood has eight to 12 false alarms per year, Cogswell says — in part because there is a lot of turnover among personnel. What Cogswell would like to see is “a national retail association or someone like that, that would get on board and say we could save a bunch of money just by doing this one simple thing.”

Martin sums up the false alarm situation well when he says, “It feels like the industry is firing on all cylinders now, but we can’t ever stop or slow down.”

SIDEBAR: Resources

A wealth of information to help reduce false alarms is available on the Internet:- Alarm Industry Research Educational Foundation (www.airef.org)

Use this source for the results of a 2006 survey that showed widespread alarm industry opposition to verified response. - Central Station Alarm Association (www.csaaul.org)

Offers false alarm analysis software and a free online false alarm training class. - False Alarm Reduction Association (www.faraonline.org)

- Includes profiles of communities that have had success in reducing false alarms, along with model ordinances and consumer tips.

- National Burglar & Fire Alarm Association (www.alarm.org)

- Offers questions and answers about false alarm reduction and a model ordinance in its “public safety” section.

- Security Industry Alarm Coalition (www.siacinc.org)

Includes a wealth of information, including a list of UL-compliant CP-01 panels, briefing papers on enhanced call verification, a survey of Salt Lake City citizens that shows wide opposition to verified response, a model ordinance, advice on how to set up an alarm school and free alarm tracking software.