|

| Laura Stepanek |

The security community in Illinois has its own self-described pit bull and I don’t think he’d mind if I called him out — president of the Illinois Electronic Security Association (IESA), Chet Donati. He also is owner of DMC Security Services in Midlothian, Ill.Illinois is home to some tough characters, many of whom are under the spotlight as government office holders. A term sometimes used to describe these folks is “pit bulls.”

The fact is, sometimes you need a pit bull on your side — and this is the case in Illinois right now, because a trend is surfacing that has the potential to spread to other states. “We have piqued the interest of the entire United States,” Donati commented.

At issue is that several Illinois fire protection districts (among a total of 63 districts statewide) and Illinois municipalities are either currently engaged in or are considering monitoring private fire alarm systems of homes and businesses. In some cases, these districts or towns have set up radio monitoring equipment and have gone so far as to mandate that the fire alarm systems be monitored by them, declaring to citizens that their existing contracts with private alarm dealers are null and void.

This issue first came to light last August, and since then, IESA members have been working actively to uncover the impetus of this trend. On Jan. 19, EMERgency 24 hosted an IESA meeting at its Des Plaines, Ill., headquarters at which approximately 120 people attended — more than four times the usual meeting attendance. Kevin Lehan, manager of public relations at EMERgency 24, also serves as IESA’s executive director.

In his opening comments at the meeting, Lehan described a scenario in which communication between PSAPs (public safety answering points) and city councils depicts central stations as unnecessary “middlemen” that exist between citizens with fire alarm systems and first responders — some districts even going so far as saying that central stations take up to 15 minutes to dispatch a fire alarm.

“The main point of [their] sales pitch,” Lehan said, “is to use code experts that work as consultants to distort the true meaning of the code. Those code experts go to the PSAP leaders, give them a sales pitch, which then go back to their city councils and say, ‘You know, this is a great idea. We should get into this in the name of public safety. But still, think of all that revenue!’ It is a money-making proposition,” Lehan said, pointing out that with so many municipal governments operating in a deficit, it’s no wonder that the idea of getting into the monitoring business is appealing to them.

One memo, for example, stated: “The alarm company is the middleman. Claim that revenue for yourselves.”

To date there has been at least one victory for the alarm industry in its ability to temporarily prevent a district from taking over monitoring, yet other battles remain to be fought (See SDM, January 2011, p. 17). Other districts have backed away from their initial idea of offering monitoring, citing cost considerations.

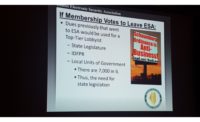

Some IESA members believe it is not in a fire protection district’s purview to profit from public safety. Richard Lockhart of Social Engineering Associates Inc., IESA’s long-time lobbyist, said he expects new legislation to be introduced in Illinois this month, which would effectively give fire protection districts the legal right to establish such profit centers. IESA outlined an action plan to oppose the legislation.

“I am not going to roll over and play dead on this one,” Donati said, adding that neither are other Illinois alarm dealers and central stations. “We are in it to win it and it’s not going to take a minute. We’re going to fight it all the way. And if anybody doesn’t believe that, trust me; I can be the best pit bull in the yard that you ever want to see.”